Main Sections

Protected Areas

Protected areas, which include parks and ecological reserves, are created to protect the natural environment, cultural heritage and recreational values of the province.

BC’s Protected Areas Strategy has two goals. The first goal is to protect viable, representative examples of the natural diversity of each ecosection. These can include the main terrestrial, marine and freshwater ecosystems, the characteristic habitats, hydrology and landforms, and the characteristic recreational and cultural heritage values.

The second goal is to protect special natural, cultural heritage and recreational features. These can include habitat for rare and endangered species, outstanding or unique plant, animal, mineral or fossil features, and important cultural heritage or recreational sites.

Protected areas are open to a more limited range of commercial activities than surrounding Crown lands. Under the guidance of local management plans parks offer opportunities for range and tourism use. Commercial logging, mining and energy development are, however, not allowed.

Different parts of protected areas can be managed for different types of use. Management categories include strict preservation, wilderness, natural environment-based outdoor recreation, intensive recreation and tourism, and historical, cultural and heritage use.

Table 1:

Existing Protected Areas (approximate size in hectares)

| Duffey Lake Park | 2,010 | Skihist Ecological Reserve | 35 |

| Goldpan Park | 5 | Skihist Park | 35 |

| Marble Canyon Park | 550 | Skwaha Lake Ecological Reserve | 850 |

| Seton-Portage Historic Park | 1 | Stein Valley Nlaka’pamux Heritage Park | 107,190 |

| Bridge River Delta | 970 | Marble Canyon (park extension) | 2,300 |

| Cerise Creek | 1,380 | Skihist (park extension) | 360 |

| Fred and Antoine Creeks | 8,300 | South Chilcotin (Spruce Lake) | 56,540 |

| French Bar Creek | 1,130 | Yalakom Creek | 8,950 |

Notes: 1) Arthur Seat (~2,340 ha) will remain a Cabinet-approved study area while discussions with First Nations continue.

To assist the planning and management of the protected areas in British Columbia, zoning is used. That means that zoning divides an area in different units to achieve the most protective value of a area. Every zone appeals to something different for instance the intended land use, the existing patterns of use, the degree of human use desired and the level of management and development. For visitors and managers each section represent on how a singular area is managed. Zoning is an essential requirement for all protected areas except for ecological reserves. There are six possible zones that can be used in protected areas:

- Special Natural Feature Zone

- Cultural Zone

- Intensive Recreation Zone

- Nature Recreation Zone

- Wilderness Recreation Zone

- Wilderness Conservation Zone

The different sections are determined after objective, use level, access, location, size, recreation opportunities, impact on environment and examples of such a zone.

Source: BC Parks Zoning Framework

Issues:

- Achieving a balance between ecological integrity and public and commercial use within protected areas.

- Overuse and/or inappropriate use can impair or spoil the ecological integrity of protected areas.

- Access management within protected areas needs to allow a variety of public uses, while ensuring tenured access and avoiding general overuse.

- Managing public and commercial recreation uses within protected areas to ensure maximum compatibility.

- First Nations, local government, the public, and user groups seek greater involvement in park planning processes.

- Integrating park designation and management with preexisting rights and tenures, such as livestock grazing and commercial recreation.

- By preventing access to irrigation water protected areas can preclude future development of some Crown lands with agricultural potential (e.g., French Bar Creek).

- Unclear land and resource management direction can limit resource development opportunities adjacent to protected areas.

- Forest fire, pests and disease are part of nature and are integral to protected areas. If not recognized and addressed they can damage nearby timber harvesting areas thus increasing operating costs or disrupting timber supplies.

Goals:

- Protect representative and special natural places for conservation, outdoor recreation, education and scientific study.

- Protect natural environments for the inspiration, use and enjoyment of current and future generations.

- Provide opportunities for a diverse, high quality and safe outdoor recreation while ensuring protection of the natural environment.

- Achieve a balance between ecological integrity, public recreational use, scientific study, and commercial opportunities (e.g., tourism, grazing), in protected areas.

Grasslands are open landscapes where grasses or grass-like plants dominant the habitat. They cover less than 1% of British Columbia, but provide habitat for over 30% species at risk.

A few important roles that grasslands provide include erosion protection, water regulation, filtration and supply, as well as protection from drought and flood. Grasslands are habitat for wildlife, including at-risk species. We need these habitats of the pollination for agriculture and local food supply. They are also important for tourism (hunting, fishing, mountain biking, wildlife viewing, backpacking and camping), and providing recreation and cultural opportunities.

When a grassland is once lost is the service often lost forever and it’s very difficult to replace them. To let it rest is the best way to restore a grassland that process can take several decades.

Grasslands are the most dramatically affected ecosystem on earth because of humans. They covered one time 40% of the North America continent. Today there are less than 1% remaining.

Local governments are beginning to protect grasslands in British Columbia through parks and natural areas policy, and open space areas in respect of grassland ecosystems such as mature forest and old growth forest. Some are working on partnerships to share knowledge and resources for rice environmental planning.

Kamloops created an Aberdeen area plan, contain to growth to protecting areas deemed high priority for conservation and compression areas of grassland.

To conclude, the grassland projects high priority is to conserve, restore and protect grasslands in British Columbia. The projects are important for tourism, conserving habitat for wildlife species, and our food supply.

It’s all one circulation of nature.

Source: Grasslands

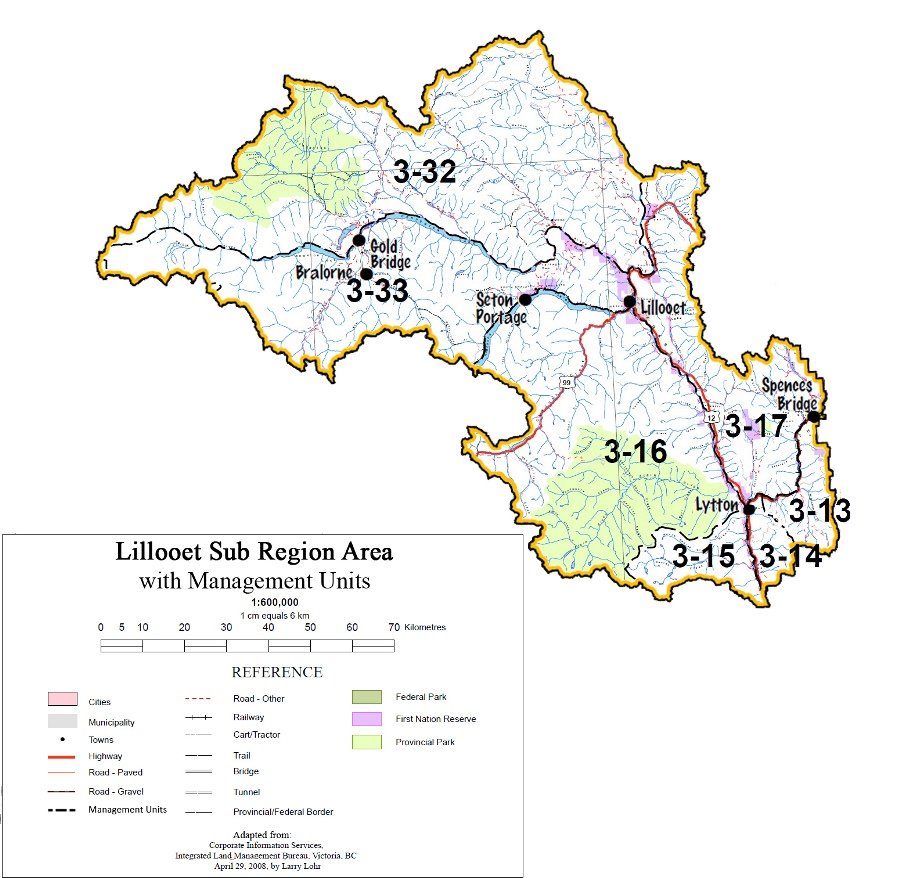

Protected Areas

- Duffey Lake Park

- Marble Canyon Park

- Goldpan Park

- Bridge River Delta Park

- Seton-Portage Historic Park

- Yalakom Creek Park

- South Chilcotin Mountain Park

- Stein Valley Nlaka’pamux Heritage Park

- Skwaha Lake Ecological Reserve

- Skihist Park

- Skihist Ecological Reserve

- Gwyneth Lake Park

- French Bar Creek Park

- Fred Antoine Park

- Cerise Creek Park

- Grasslands in British Columbia

| Objectives | Management Direction/Strategies | Measures of Success/Targets | Intent |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Manage park use to conserve ecological values | 1.1 Disperse use to less heavily used areas as may be allowed by park management plans | Under-represented ecosystems protected Fish, wildlife and critical habitat protected | |

| 1.2 Use local level plans to manage general public and commercial recreation use and access in order to preserve ecological values | |||

| 1.3 Ration park use by permit if necessary to meet management objectives for ecological integrity | |||

| 2. Complete park management planning on a priority basis | 2.1 Develop plans (e.g., management direction statements; park management plans) to guide the management of protected areas | Park management direction statements completed within two years of legal establishment | |

| 2.2 Ensure the public is involved in park management planning | |||

| 2.3 Encourage participation in plan development by interested stakeholders (both regional and provincial) | |||

| 2.4 Ensure that management plans incorporate LRMP direction with respect to the theme and purposes of each park (see Table 3) | |||

| 3. Manage park use to maintain the quality of visitor experience | 3.1 "Harden” park facilities (e.g., trails and campsites) in a way that prevents site degradation but conserves a natural appearance | Park visitor satisfaction | |

| 3.2 Manage general public and commercial recreation use and access in order to maintain the quality of visitor experience | |||

| 3.3 Ration park use by permit if necessary to meet management objectives for the visitor experience | |||

| 4. Manage types and modes of recreation to minimize conflicts among users | 4.1 Zone different portions of protected areas for various modes of access consistent with the LRMP and the goals for each park | Park user-days | |

| 4.2 Develop an equitable allocation process between commercial and noncommercial users, consistent with government protocols and park management planning processes | |||

| 5. Manage protected areas to achieve a balance between ecological integrity, commercial tourism opportunities, and general park visitors | 5.1 Through park management planning processes: develop appropriate limits of capacity on a park by park basis, considering the overall management direction for the park and/or for the zones within the park (e.g., if the park has a conservation focus then a conservative carrying capacity would be appropriate; conversely, if the management direction is for intensive recreation then a less conservative carrying capacity could be used) distinguish limits relative to tourism clients and general park users consider resource allocations between tourism clients and general park users; and apply consistent approaches (e.g., reservation systems, registration and fees) to managing both commercial tourism clients and public users | Commercial / public user conflicts resolved | |

| 5.2 Include all interests and the general public in park management planning processes to address use capacity levels, environmental sustainability and the quality of the park experience | |||

| 6. Honour preexisting rights and tenures in new protected areas | 6.1 Since logging, mineral and energy exploration and development are not allowed in protected areas, provide prompt and fair compensation for forest, mineral and energy tenures included in them, consistent with government policies | ||

| 6.2 Issue park use permits when authorizing the continuation of existing liens, charges, and encumbrances (other than those prohibited by legislation and policy). | This recognizes Land Act tenures, special use permits, water rights, trapping licenses and other legal tenures and rights that are allowed in protected areas | ||

| 6.3 Continue pre-existing water licenses that may include domestic, irrigation, diversions and water storage structures. Continue these licenses and the ability to manage them for their licensed use. Ensure that protected area management plans allow for the continued access, maintenance and rehabilitation of water tenures | |||

| 6.4 Existing utilities, such as transmission lines, pipelines and communications sites will be allowed to continue | |||

| 6.5 Allow existing grazing in protected areas | |||

| 6.6 Continue pre-existing uses, rights and tenures of established tourism operators and ensure that park management plans allow for continued access and maintenance needed by these operators | |||

| 7. Ensure that uses that are compatible with protected area designation, and which predate its legal designation (e.g., hunting, fishing, various types of recreation), continue to be accommodated within the protected area | 7.1 Accommodate pre-existing, compatible uses in the management plan of the park | ||

| 7.2 Where necessary, designate zones within parks to separate incompatible uses | |||

| 8. Ensure that the time periods, quality or type and amount of access are consistent with the objectives and prescribed character of the protected area | 8.1 Continue current methods of access to existing tenures, subject to periodic review of their appropriateness in light of changing conditions. Address further access management concerns in protected area management planning | ||

| 8.2 Coordinate access planning jointly between managers of parks and adjacent lands to avoid conflicts | |||

| 8.3 In protected areas having existing or potential tourism operations, and where tourism is an acceptable use, determine the desirability, necessity, location and type of access in park management planning | |||

| 8.4 Ensure that park management planning addresses motorized and nonmotorized use | |||

| 8.5 Ensure that the rights of way for roads that are excluded from protected areas are sufficiently wide enough to accommodate maintenance, realignments, management of hazard trees, etc. | |||

| 8.6 Allow continued access for maintenance of existing water and weather data collection stations (e.g., snow courses, snow pillows, stream gauges) in new protected areas | |||

| 9. Manage forest health factors (e.g., disease, insect infestation, noxious weeds) to an acceptable risk level, where they pose a significant risk to resources and/or values | 9.1 For each protected area, assign forest health objectives and strategies that are consistent with its purpose. Include fire management strategies | The “acceptable risk level” will be determined on a sitespecific basis between BC Parks and Ministry of Forests | |

| 9.2 Through inter-agency cooperation, protected areas will be monitored for forest health factor indicators in conjunction with adjacent, nonprotected areas | |||

| 9.3 Where there is a low risk from forest health factors no human intervention is necessary | |||

| 9.4 Where there is a significant risk from forest health factors, management should follow direction from BC Parks, and consider the potential impact to resources and values within and external to the protected area | |||

| 9.5 Monitor and control weeds consistent with current policies and guidelines. Work cooperatively with other agencies | |||

| 10. Manage preexisting Range Act tenures in new protected areas as prescribed in the Park Amendment Act | 10.1 Manage grazing under preexisting Range Act tenures in new protected areas under appropriate guidelines | ||

| 10.2 Manage ungrazed areas in suitable new protected areas | |||

| 11. Evaluate suitability of protected areas as sources of irrigation water for adjacent agricultural land | |||

| 12. Consider Table 3 “Management Categories and Key Issues” in management plans for new protected areas |

Table 3

New Protected Areas: Selected Features, Management Categories and Key Issues

| Name | Selected Features | Management Categories and Key Issues |

|---|---|---|

| Bridge River Delta | Valley bottom/braided stream ecosystems Critical habitat for grizzly bears | Natural environment; strict preservation Balancing conservation of grizzly bear habitat with use of area (grazing; trappping; hunting) |

| Cerise Creek | Popular mountaineering area (summer and winter) adjacent to Joffre Lakes Provincial Park Grizzly bear and mountain goat habitat | Natural environment Balancing conservation of bear and goat habitat with use of area (recreation) |

| Fred and Antoine Creeks | Under-represented ecosystems (dry forests) First Nations cultural artifacts | Natural environment; wilderness Access for owners of private land and water rights Access into the park needs improvement |

| French Bar Creek | Under-represented ecosystems (dry forests; grasslands) Bighorn sheep migration route | Natural environment Establish under Environment and Land Use Act to allow: (a) future development of water resources for agriculture, and (b) future roads, pipelines or infrastructure along Fraser Canyon |

| Gwyneth Lake | Small lake for destination and day use of motorists on Hurley-Carpenter Lake Road | Intensive recreation |

| Marble Canyon | Rock and ice climbing Fishing Geological history | Natural environment Allow right of way for improvements on Highway 99 Access for owners of private land |

| Skihist Park Extension | Extension to popular park beside Trans Canada Highway Hiking trails Under-represented ecosystems (dry forests) | Natural environment |

| South Chilcotin (Spruce Lake) | Transition from wet coastal to dry interior ecosystems Adjoins Big Creek Park Wildlife habitat (grizzly bear; bighorn sheep; mountain goats) Wildflowers Broad valleys and interconected alpine basins suitable for long backpacking or horse riding trips Well-preserved Mesozoic marine fossils | Wilderness; natural environment Balancing conservation of grizzly bear, sheep and goat habitat with use of area Integrating commercial recreation businesses with public use (winter and summer) Access for owners of private land Scientific research and collection of fossils Public snowmobile users need assured access into Upper Slim Creek |

| Yalakom Creek | Undeveloped watershed Old growth forests Bighorn sheep habitat and migration route | Wilderness Balancing conservation of sheep habitat and migration routes with use of area |